Stone sculptures began in India about 2200 years ago with the depiction of Buddhist art stories that we know as Jataka Tales. Before this, the art must have existed but on perishable material like wood that has not survived the times.

Earliest stone sculptures are attributed to the sites of Barhut near Jabalpur in MP and Sannati-Kanganahalli near Gulbarga in Karnataka, quickly followed by many sites spread all across the Indian subcontinent.

Buddhist Art Narration

In this post, I will talk about 7 different modes adopted by the artists of that era to depict Buddhist art stories in stone. These stories primarily came from the Jatakas – which are stories of Bodhisattvas. About 550 such stories exist but most artists chose to depict a few stories repeatedly.

Stories or scenes from the life of Buddha are the second most common depictions we find in stone. Followed by some stories of post–Buddha times that primarily include visits to Buddha sites by prominent kings who also contributed to

Followed by some stories of post–Buddha times that primarily include visits to Buddha sites by prominent kings who also contributed to the erection of these sites. All art is typically around a Stupa – which is a hemispherical mound that holds Buddha’s relics casket at the base of it. It has a circumambulation path or Pradakshina path around it. Marked by a stone railing that usually has a crossbar pattern. Sometimes with carved stones and sometimes plain. Without getting into the architecture of Stupa, let me get into the story-telling styles in early Buddhist Art.

Read about the Jatakas. And some of the Jatakas mentioned in this post: Vessantara Jataka, Dipankara Jataka, Mahakapi Jataka, Nanda Jataka & Simhala Jataka.

Monoscenic Narrative – Theme in Action

This is the simplest mode of telling the story. Artist picked up the highlight of the story or one episode and carved it in stone. Usually, they did not take the beginning or the end of the story. But the high action point of the story.

Art historians conclude that artists assumed the viewers’ familiarity with the story. Hence only the high point was highlighted to remind them of the story. For example, at Barhut the Artist depicts the Vessantara Jataka through the depiction of only one scene. Where Vessantara donates his prosperity by giving a white elephant to a Brahman to highlight the virtue of charity.

Monoscenic Narrative – Being in State

In this mode instead of depicting action, the outcome of the story is depicted. I interpret this as depicting the moral of the story. Again, assuming that the viewer knows the story well.

This mode of narration has been used to depict the states of Buddha after say he achieved enlightenment or just before his Mahaparinirvana. He is the supreme figure in the narrative. Take this example from a Barhut pillar where the descent of Buddha from heaven at Sankissa is depicted through the footprints on a ladder.

Sequential or Liner Narrative

Sequential episodes of the story are depicted in a linear or sequential fashion, with the protagonist repeating in every scene. Scenes are clearly demarcated from each other.

An example of this is the story of Nanda Jataka depicted at Nagarjunkonda with scenes clearly demarcated with pairs of pillars with amorous couples. Historians are still figuring out the relevance of these punctuation marks in the narrative. This is the mode that is easiest to understand and almost intuitive to our modern sensibilities.

Continuous Narrative in Buddhist Art

Multiple scenes of a story with the protagonist repeated are shown within a single frame. A scene of the Great departure of Buddha on a crossbar of arches in Sanchi uses this mode. The horse with a parasol depicts the departure of Siddharth from his palace. Then, the empty horse returning back shows the staying back of Buddha.

Here the scenes are carved in continuity and have no clear demarcation. It’s the repetitive depiction of the horse that shows the movement of the narrative.

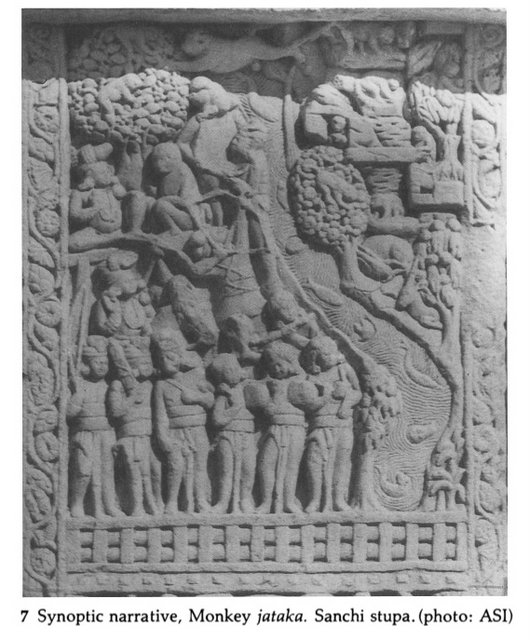

Synoptic Narrative

Multiple scenes of a story are shown within a single frame. But without indicating any chronological order of the story. The protagonist tends to repeat in all the scenes. Lots of stories are depicted within a limited space of a roundel or a rectangular tablet either as part of a pillar or larger panels have these stories.

Take the case of Mahakapi Jataka from a pillar panel at Sanchi Stupa. The sequences in the story can be very confusing unless you know the story very well and can relate to the scenes. Art historians have tried to put numbers on the sketches of some of these narratives to explain but that does not tell us why did the artists choose this mode. It is a given they assumed familiarity with the story, but why disregard the chronology or flow of the story?

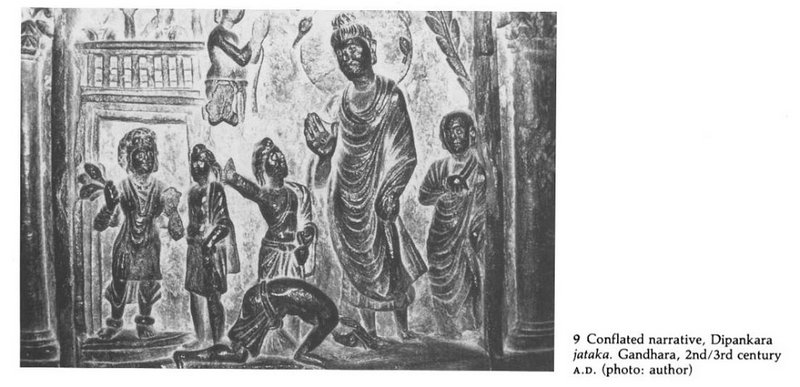

Conflated Narrative

This is Similar to the synoptic narrative. But with a single conflated depiction of the protagonist while the story gets revealed around this large figure. In other words, in this mode, the protagonist does not repeat, but the story is depicted around him.

An example of the Dipankar Jataka from a Gandhara panel is a good example of this with a towering figure of Buddha around which the story of Sumedha moves.

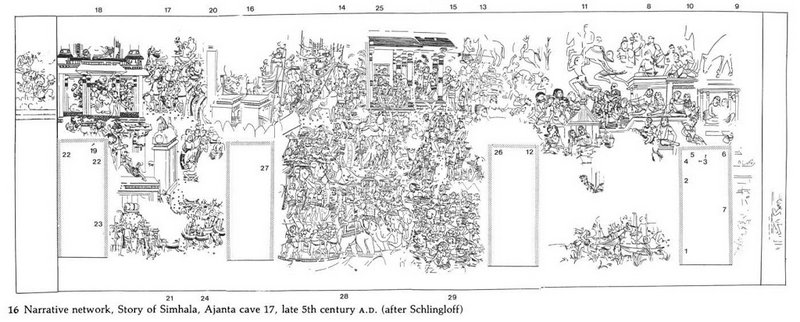

Narrative Networks in Buddhist Art

The story is depicted as a network of scenes. With scenes scattered across the available space that follow no chronological order, leaving a lot to the interpretation of the viewer. However as Prof Dehejia explained in her lecture – the artist was following a spatial narrative than a chronological narrative. That means that scenes that were happening in a given space were depicted in one place.

The scenes that were happening at another place were clustered together. So you have to follow the story and move across spaces. Most paintings in Ajanta follow this complex narrative network mode. For example, Simhala Jataka is depicted in cave 17 at Ajanta in 29 scenes on a 45 feet wall that is 13 feet high from floor to ceiling. Imagine the complexity and add to this the fact that it is pitch dark inside those caves to paint.

Remember visual narratives in stone are following the oral tradition. They pre-date the written text making them an important milestone in the journey of storytelling.

This post on Buddhist art is based on the short course ‘Visual Narratives in early Buddhist Art’ conducted by Prof Vidya Dehejia. I took her permission to write this post based on her work. 6 of the 7 pictures have been taken from the material provided by Goa University. I am using them only to illustrate the various modes of Buddhist Art, for the reader to understand them clearly. If there is any copyright misuse because of this – please let me know. I will remove the images as soon as possible. Do check out the images at various sites like IGNCA, Art, and Archeology, MetropolitanMuseum, British Museum for thousands of visual narratives of which the above is just an indicative sample.

Beautifully explained. Your clear narration of the narratives makes it quite obvious that there is nothing to beat sequence and chronology in story telling even if one is familiar with the content. But one can’t but salute the artists and craftsmen of those times for the gems of visuals and stories they have left for us.

Great reading this lovely and very lucidly explained post about the Buddhist narrative art and you are so lucky to have done the course with Dr. Vidya Dehejia whom I have also heard her talk on different topics in Mumbai. Before the stone there was probably the wooden artwork which has not survived the ravages of time except in some of the rock cut caves in Maharashtra.

Yes, Dr Dehejia is too good with her subject and a teacher par excellence. With teachers like her we all would be connoisseurs of Arts.